"A Song of Confidence: God Is Always With Us"

"A Song of Confidence: God Is Always With Us"1. In two distinct moments, the Liturgy of Vespers -- on whose psalms and canticles we are meditating -- proposes to us the reading of a sapiential hymn of transparent beauty and of intense emotional impact, Psalm 138(139). Before us we have today the first part of the composition (cf. 1-12), that is to say, the two first stanzas that exalt, respectively, the omniscience of God (cf. 1-6) and his omnipresence in space and time (cf. 7-12).

The vigor of the images and the expressions have as their objective the celebration of the creator: "If the created works are so great," affirmed Theodoret of Cyrus, a Christian writer of the fifth century, "how great the creator must then be!" ("Discorsi sulla Provvidenza," 4: "Collana di Testi Patristici," LXXV [Discourse on Providence: Compilation of Patristic Texts] Roma 1988, p. 115). The meditation of the psalmist seeks above all to penetrate into the mystery of the transcendent God, who at the same time is close to us.

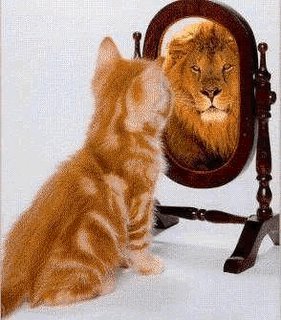

2. The essence of the message that is presented to us is clear: God knows everything and he is with his creature, and it is not possible to elude him. His presence is not threatening nor controlling, even though his gaze certainly is grave when looking on evil, before which he is not indifferent.

Nonetheless, his fundamental element is of a salvific presence, capable embracing all of being and all of history. In short, it is the spiritual setting to which St. Paul alludes when speaking in the Areopagus of Athens, when he quoted a Greek poet: "In him we live and move and have our being" (Acts 17:28).

3. The first passage (cf. Psalm 138[139]:1-6), as he says, is the celebration of the divine omnipresence: In fact, the verbs of knowledge such as "to probe," "to be familiar with," "to understand," "to distinguish" and "to know" are repeated. As is it known, biblical knowledge goes much further than mere intellectual learning and understanding; it is a type of communion between the knower and the known: The Lord is, therefore, intimate with us, in our thoughts and actions.

The second passage of the psalm is dedicated to the divine omnipresence (cf. verses 7-12). In this verse, the illusory will of man to elude the presence of God is described in a palpitating way. All of space is embraced: above all, the vertical axis of "heaven-abyss" (cf. verse 8), and then the horizontal dimension, everything from the dawn, that is to say, from the East, to "beyond the sea," the Mediterranean, that is to say, the West (cf. verse 9). In each one of these spheres of space, including the most secret, God is actively present.

The psalmist also introduces the other reality in which we are submerged, time, symbolically represented by night and light, shadows and day (cf. verses 11-12). Even darkness, in which it is difficult to advance and see, is penetrated by the gaze and by the presence the Lord of being and of time. He is always willing to take us by the hand to guide us on our earthly path (cf. verse 10). Therefore, it is not a closeness of a judge that provokes terror, but rather of support and freedom.

In this way, we are able to understand the ultimate, essential content of this psalm. It is a song of confidence: God is always with us. Even in the dark nights of our life, he does not abandon us. Even in the difficult moments, he is present. And even in the final night, in the final solitude in which no one will be able to accompany us, in the night of death, the Lord does not abandon us. He accompanies us, as well, in this last solitude of the night of death. And for this reason, as Christians, we can be confident: We are never alone. The goodness of God is always with us.

4. We began with a quote of the Christian writer Theodoret of Cyrus. We end now commending ourselves to him and to his "Fourth Discourse on Providence," for this is definitively the theme of the psalm. He reflects on verse 6, in which the psalmist exclaims: "Such knowledge is beyond me, far too lofty for me to reach." Theodoret comments on this passage analyzing in depth in the interior of his conscience and personal experience and affirms: "Recollected and entering into my own intimacy, removing myself from external murmuring, I wanted to submerge myself in the contemplation of my nature. ... Reflecting on this and thinking of the harmony between mortal and immortal nature, I was startled by such wonder, and when I could not contemplate this mystery, I recognized my failure; and what's more, while I proclaim the victory of the knowledge of the Creator, and sing to him songs of praise, I cry: 'Such knowledge is beyond me, far too lofty for me to reach'" ("Collana di Testi Patristici" [Compilation of Patristic Texts] LXXV, Rome, 1988, pp. 116, 117).

No comments:

Post a Comment